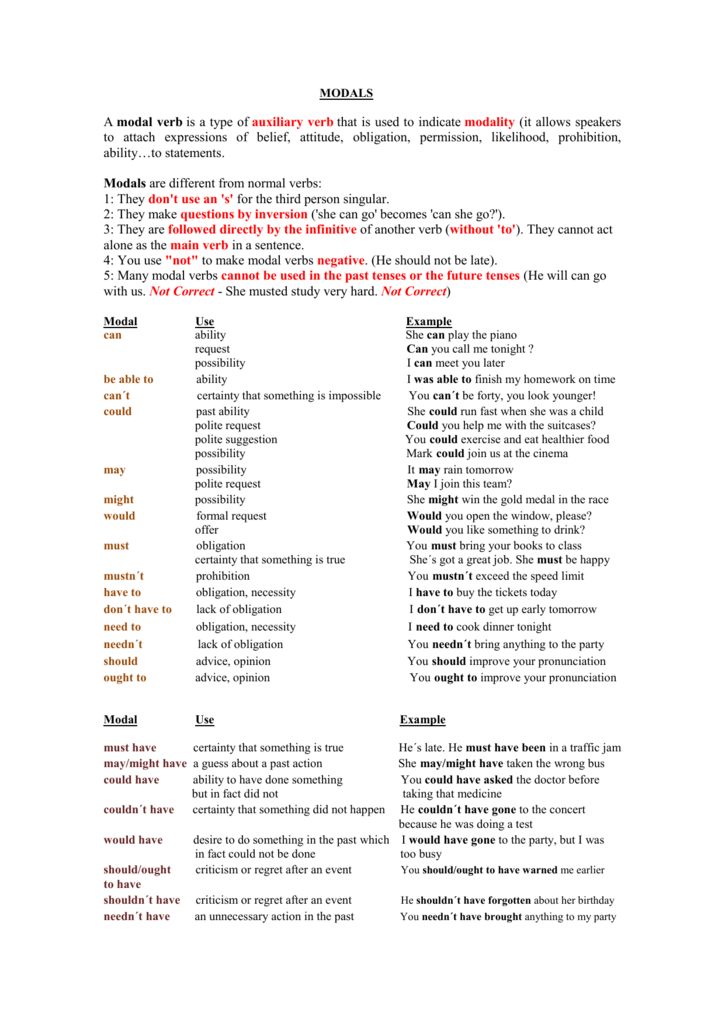

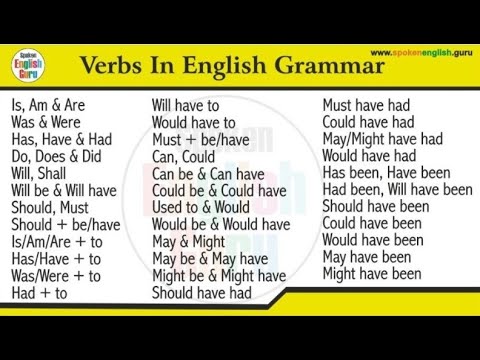

In English, modality is primarily conveyed through modal auxiliary verbs such as can, could, will, and must, among others. Certain modal verbs can serve several modality functions. English modals are not inflected for person or number agreement with the subject. In some instances, these distinctions correspond directly with events in time, as in can/could in I can run the mile in six minutes, but when I was younger I could run it in five minutes. However, the correspondence between formal tense and events in time is not straightforward, as we discuss below. Have to and have got to break all of the rules that pure modal auxiliary verbs follow.

They consist of more than one word, they use infinitive forms of the main verbs, the auxiliary verb do is used for negatives and questions , and they conjugate for the third-person singular. Despite all of these differences, these semi-modal auxiliary verbs have several modal meanings. Modal verbs and auxiliary verbs are two different types of verbs, and between which some differences can be highlighted. The modal and auxiliary verbs are two such categories. These are a type of auxiliary verbs used when making requests, speaking of possibilities, etc.

On the other hand, auxiliary verbs are also known as helping verbs. One of the key differences between the two types of verbs is that while auxiliary verbs have to be conjugated, modal auxiliary verbs do not. This article attempts to highlight this difference in detail.

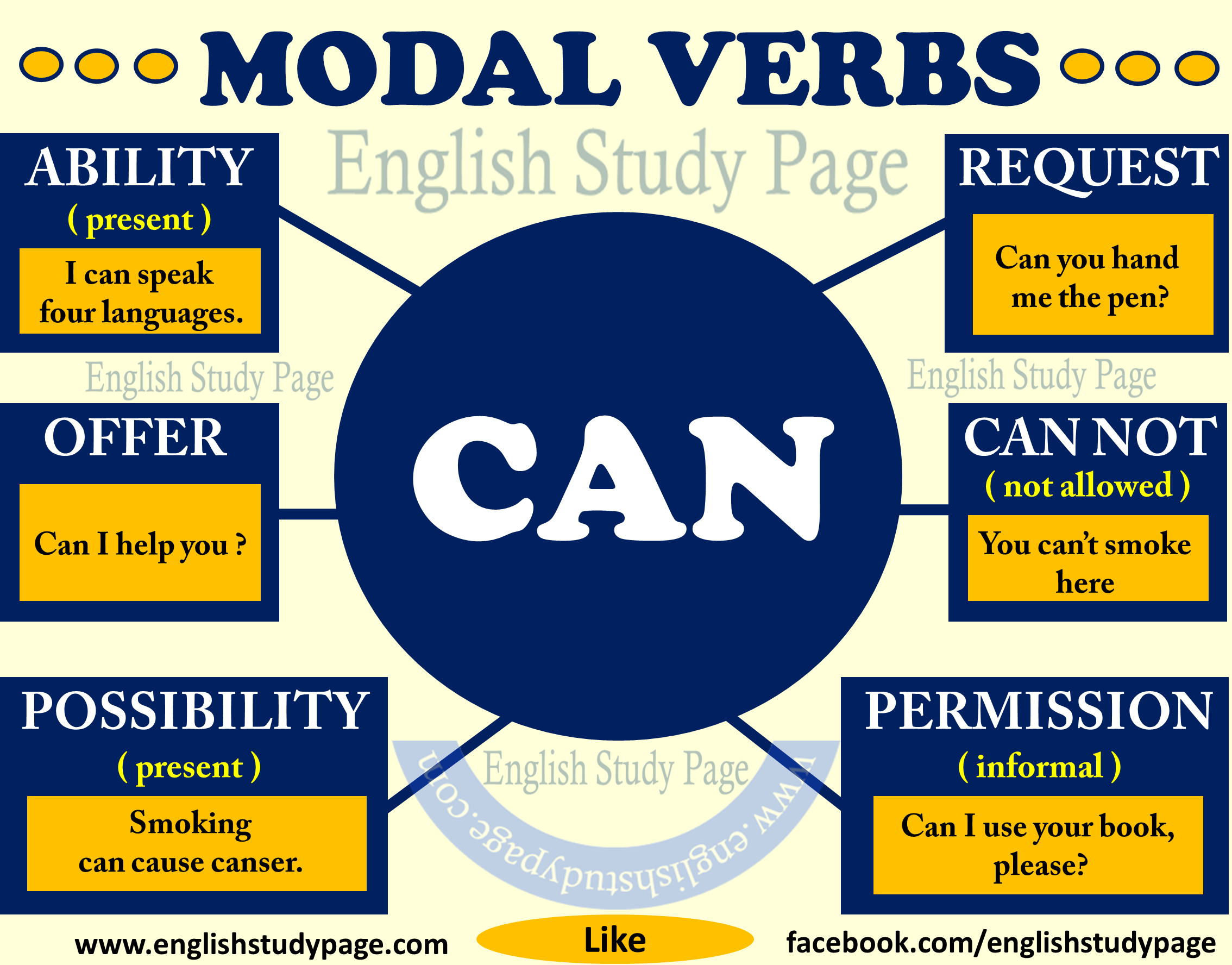

Modal auxiliary verbs, also commonly referred to as modal verbs or modals, are used to shift the meaning of the main verb in a clause. These shifts include expressing possibility, ability, permission, obligation, or future intention. Students can find these confusing because one modal auxiliary verb can have multiple meanings depending on the context.

Several studies have been directed at English-speaking children's early use of modal verbs. According to the work of Wells , Kuczaj , and Richards , can seems to emerge earlier and is used more frequently than other modals, with the exception of its negative counterpart, can't. The modal can is often used in interrogatives to request permission. In declaratives, can is used most frequently to express the notion of ability, though often this use falls somewhere on a continuum between ability and circumstantial possibility . It appears that can is the first modal to be used by children to express these notions, and each of these notions is expressed by age 2;6 . Papafragou has suggested that notions such as ability and permission are acquired earlier than functions that reflect epistemic modality because they do not require children to reflect on their own mental states.

In this context, we expect that probability modal verbs entailing tentativeness will occur more frequently in introductions and necessity modals should appear more frequently in conclusions. Research on the use of modal verbs in these two sections of the research article has been conducted using corpus tools for text retrieval and analysis. Variation ratios will be evaluated using a log-likelihood test to determine the significance of variation according to whether specific modal meanings appear in the introductions or the conclusions. Our main research questions are 'How does the use of modal verbs vary in the introduction and conclusion sections of scientific tourism research articles in terms of form and meaning? ' and 'How does the use of modal verbs vary in the introduction and conclusion sections of scientific tourism research articles in terms of the functions they fulfil? This pattern of findings suggests a three-step process for intervention aimed at assisting children in their acquisition and use of modals.

First, clinicians might provide children with a modal form for each of the major modality functions served by modals in the child's language. Otherwise, children might unduly restrict their use of particular modal forms (e.g. can only in permission contexts, could only in possibility contexts). Finally, children may need assistance in learning and using two different modal forms when the same modality function (e.g. ability) must be used in past as well as non-past contexts. Determination of the procedures most appropriate for these intervention goals must be discovered through future research. However, given the general success shown by the OTD children in the present investigation, the types of contexts employed here might be considered as a useful starting point.

In Cantonese, modals usually appear before the main verb, as in English. The morphemes serving as modals are not marked for tense and do not change as a function of the present or past nature of the event. In this study, we examined children's use of two modals, sik1 and ho2ji5. The modal sik1 expresses ability, and is similar to can when used in contexts meaning 'is able to' or 'knows how to'. The modal ho2ji5 is used in contexts pertaining to permission.

Although Cantonese and English can convey essentially the same modality functions, Cantonese differs from English in how these functions are divided among the modals of the language. The modal ho2ji5, frequently used for permission, can be extended to the function of possibility. However, it does not convey the sense of ability, unlike English can which is applicable to ability as well as permission and possibility. Research has been conducted using corpus tools to obtain evidence from our sub-corpus of introductions and conclusions, as mentioned earlier. Direct visual inspection of the texts has also been vital to identify the meaning of the modal verbs in context.

The fundamental role of the context in specifying the sense a particular modal verb entails has been mentioned in the literature (see Huschová, 2015; Alonso-Almeida, 2015a and the references therein). A modal verb may indicate an array of meanings, and therefore without these contextual cues, it would be unreasonable to expect an accurate categorisation of these verbal forms. The plasticity of modal verbs makes them unique; however, it also challenges our ability to identify the meanings they involve each time. The semi-modal auxiliary verb ought to ends in to, which makes the main verb an infinitive. This differs from pure-modal auxiliary verbs, which use the bare infinitive, the infinitive without to, for the main verb. The meaning of ought to is nearly the same as should in all cases.

When forming questions or negatives, should is more commonly used than ought to. We can think of three ways to examine modal use in a manner that separates modality and formal tense to the greatest extent possible. The first, pursued in Study 1, is to examine children's use of different modality functions that can be expressed using the same modal with the same tense value (non-past). The second, explored in Study 2, is to examine the use of modals by children with SLI when tense is clearly not involved. Notions of past time, for example, must be established by means other than by verb tense, such as by use of temporal adverbs.

Therefore, unlike English modals, any difficulty that Cantonese-speaking children with SLI exhibit in the use of modals cannot be attributed to problems with tense. The third way is to examine children's use of the same modality function in contexts that require either a modal with the formal tense value of past or a modal with the formal tense value of non-past . In all three studies, children with SLI are compared to a group of typically developing same-age peers and a group of typically developing children approximately two years younger. Last but not the least, when the teaching context changes where the learners are intermediate or higher learners, the use of grammar used in different context will be explained to the students. As Ivanovska mentioned that the students' task is to manipulate the modal verbs in particular context since "the meaning depends upon the context in which the auxiliary is used" (p. 1099).

Batstone defined this approach as a process of teaching which refers to the approach that engages learners in language use. In other words, teaching grammar should not only introduce the forms but also teach how to use accurately, meaningfully, and appropriately in different context. This approach aims at concentrating learners' attention on meanings in context. As Thornbury sated, "if learners are going to be able to make sense of grammar, they will need to be exposed to it in its contexts of use" (p. 72). Being a type of auxiliary verb, the modal verb is mainly used when speakers tend to express moods or attitudes (Ivanovska, 2014; Palmer, 1990; Sinclair, 1990). To be specific, Imre pointed out that modal verb express a variety of meanings, such as "possibility, necessity, politeness, etc" (p. 126).

Furthermore, Ivanovska added that modal verbs convey the meanings as "probability, permission, volition and obligation" (p. 1093). For instance, the modal verb can in It can be good indicated the speaker's attitude of agreement. In addition, it is noted that modal verbs could produce a particular effect, such as giving an instruction or making a request . For example, can in You can park the car here functions as an instruction. That is, it seems unlikely that they were superior to the YTD children in their ability with modality functions but were hampered by the formal tense involved with English modals. If this were the case, we would have seen differences between the SLI and YTD groups favoring the former in the present study, as tense is not involved in Cantonese.

In Study 3, we return to children's use of modals in English, this time altering the context of past versus non-past while keeping the modality function the same. In Study 2, the same modality functions were studied in the speech of SLI, YTD, and OTD groups who were speakers of Cantonese. In this language, tense is not employed, and therefore the modality function could be examined independent of formal tense. In Study 3, we again studied SLI, YTD, and OTD groups in English, to determine whether the children's expression of ability differed across past and non-past contexts. The results for can replicated the findings from Study 1. However, the children with SLI were significantly more limited than both the YTD and OTD groups in their use of could.

The present study examines modal verb meanings and variation in these verbs in a corpus of texts in the field of tourism. We use a compilation of article introductions and conclusions written in English and published in leading journals specialised in tourism studies. Modal verbs are important to evince the authors' stance concerning the propositional content (Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad & Finegan, 1999; Palmer, 2001). Variation ratios will be evaluated using a log-likelihood test to determine differences in significance between occurrences in introductions and conclusions. Our conclusions will report, therefore, on the forms, meanings and functions of modal verbs in the sections analysed.

You will see that only six of those examples contain a modal auxiliary verb (need, must, can , should, will). In what follows, many examples of modal auxiliary verbs are used to exemplify the concepts but you should not assume that such verbs are the only way of expressing modality. The other examples above contain modal adjectives , modal nouns , modal adverbs , and lexical or main verbs used to express modality . Modal verbs or modal auxiliary verbs are a type of verbs that indicates modality, i.e., likelihood, permission, ability and obligation. Some of the common modal verbs are can, could, may, might and must. In Study 1, we found that English-speaking children with SLI were less proficient than OTD children in their use of the modal can to express ability and permission.

What Are The Different Types Of Modal Verbs However, these children did not differ from a group of YTD children. In Study 3, one of our measures was the use of can in ability contexts. The results for this modal and context replicated those of Study 1.

Very similar findings emerged from Study 2, involving a comparison of Cantonese-speaking SLI, OTD, and YTD groups. The lone difference between children with SLI and YTD children came from the comparison in Study 3 of the children's use of the modal could in past contexts. We organize the discussion of our findings around four themes.

First, we consider factors that might complicate interpretation of the data, such as possible limitations in the method. We then discuss the children's apparent ability in the expression of modality functions, and whether formal tense constituted a problem for these children. We conclude with a discussion of the clinical implications of the findings. Auxiliary verbs are also referred to as helping verbs.

These verbs usually go along with the main verb, similar to modal verbs. However, at some situations, the auxiliary verbs can stand alone. An auxiliary verb usually functions within the sentence in order to make sense for the listener or reader and also to provide grammatical accuracy.

The most commonly used auxiliary verbs are as follows. The verbs/expressions dare, ought to, had better, and need not behave like modal auxiliaries to a large extent, although they are not productive in the role to the same extent as those listed here. Furthermore, there are numerous other verbs that can be viewed as modal verbs insofar as they clearly express modality in the same way that the verbs in this list do, e.g. appear, have to, seem etc. In the strict sense, though, these other verbs do not qualify as modal verbs in English because they do not allow subject-auxiliary inversion, nor do they allow negation with not.

If, however, one defines modal verb entirely in terms of meaning contribution, then these other verbs would also be modals and so the list here would have to be greatly expanded. The findings from Study 3 suggest that an even larger proportion of children with SLI seem to have special problems using modals across past and non-past contexts. This difficulty might be due to a tendency to express modality with no specification of tense, or to limited knowledge of modal forms with the proper formal tense value. At the outset of this paper, we noted that modal auxiliaries differ from other tense-related morphemes in that they serve modality functions such as ability and permission. Furthermore, the mapping between tense and past/non-past time is not straightforward for modals. That is, it seemed possible that children with SLI might produce modals that are not specified for tense.

Much of the morphosyntactic research on children with specific language impairment has dealt with finite verb morphology. For example, it is well documented that children with SLI who speak Germanic languages have extraordinary difficulties with verb inflections and auxiliary verbs that mark tense. This article mainly investigates on aspect of English grammar, modal verbs, which can be problematic for EFL learners in the Chinese teaching context.

The difficulties in language learning and teaching, and rationales why modal verbs are tough to learn are examined. Then the two teaching approaches are examined, teaching the grammar works and contexts of use, which should be focused differently according to learners' level of proficiency. The research on varying the relative complexity of teaching forms or language use needs to be further discussed in the future research. Strictly speaking, dynamic modality is confined to expressions of ability or willingness. That will limit the number of modal auxiliary verbs quite severely to can, could, will, would and be ableto for the most part .

In many Germanic languages, the modal verbs may be used in more functions than in English. In German, for instance, modals can occur as non-finite verbs, which means they can be subordinate to other verbs in verb catenae; they need not appear as the clause root. This for instance enables catenae containing several modal auxiliaries.

The modal verbs are underlined in the following table. Semi-modal auxiliary verbs like ought to, had better, have to, be able to, used to, and be supposed to can have modal meanings, but they don't follow the same rules as pure modal auxiliary verbs. It is also important to consider the types of modality that were examined in this investigation. Bybee refers to functions like ability and permission as 'agent-oriented' functions because they are about conditions that affect the state of affairs of the agent in the sentence. Other modality functions pertain to the speaker's own views on the matter. The latter functions are generally acquired later by typically developing children.

Papafragou has proposed that these other functions may be dependent on children's theory of mind. It can be seen, then, that our finding of similar expression of ability and permission by children with SLI and YTD children should not be construed as a finding that all modality functions will produce similar results. In all these cases, the modal verbs 'can', 'must' and 'should' report on the desirability of the actions described in the propositional contents of the statements in which these verbs appear.

The idea of improvement, as in above, remains strong in the use of these modal verbs in all these examples. These verbs indicate that it is essential for local tourism representatives of agents to take some actions to boost economic areas of tourist interest, which means that P done by A 'is better than' ¬P by A. It seems clear, therefore, that the pragmatic motivation of deontic modals results from a desire to suggest authority as this notion is strongly connected with credibility in science.

In English there are two types of auxiliary verb, primary auxiliaries and modal auxiliaries. The three primary auxiliary verbs are 'be', 'have' and 'do'. There are ten common modal auxiliary verbs and they are 'can', 'could', 'will', 'would', 'shall', 'should', 'may', 'might', 'must' and 'ought'. Modal verbs are auxiliary verbs like can, will, could, shall, must, would, might, and should.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.